I found that this was a challenging essay which took me some time to understand. I will start with my understanding of the essay and later describe how it resonates with my personal experiences.

Analysis of the essay

The use of the term Literalist art to describe Minimalism was initially distracting. I found that the Tate’s description of Minimalism was helpful to my understanding.

Minimalism = extreme form of abstract art developed in the USA in the 1960’s which typically composed of simple geometric shapes based in the square and rectangle.

I found that when I researched the work of the artists highlighted in the essay it was easier to understand the points that Martin Fried was making.

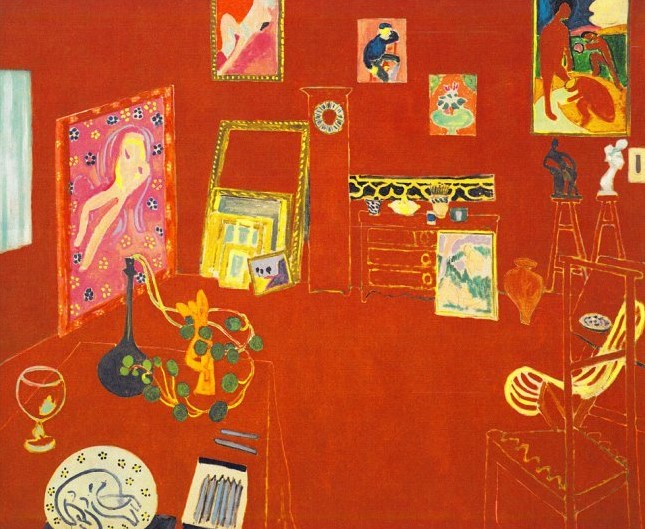

The essay starts with an explanation of what Martin considers to be literalist art and how it aspires to displace modernist painting and modernist sculpture as a way to establish itself. In many ways it is about the shape of an object. It is what it is, a whole, and not the sum of its parts. To quote from the essay ‘What is at stake in this conflict is whether the paintings or objects in question are experienced as paintings or as objects: and what decides their identity as paintings is their confronting of the demand that they hold as shapes. Otherwise they are experienced as nothing more than objects.’ The object has to suspend its own objecthood. The concept of non art is discussed and how the look of non art has moved beyond painting and onto sculpture. The term objecthood is adopted to encompass what literalist art is. However by doing this it becomes theatrical in how it confronts the beholder. The experience of literalist art is of an object in a situation. That much literalist work is large forces the beholder to keep their distance from it and be confronted by it. The object includes the beholder, large scale but not overpowering, too large. The object confronts the beholder, perhaps unexpectedly, by being in his way.

The theatricality of literalist art is inherent as the object is a statement of confrontation. In trying to explain theatre as an experience or situation as a work of art, which it isn’t, the experience of theatre is replaced by the object but the object is not there. Paintings and sculpture are not objects but by comparison literalist art assimilates objects to be art.

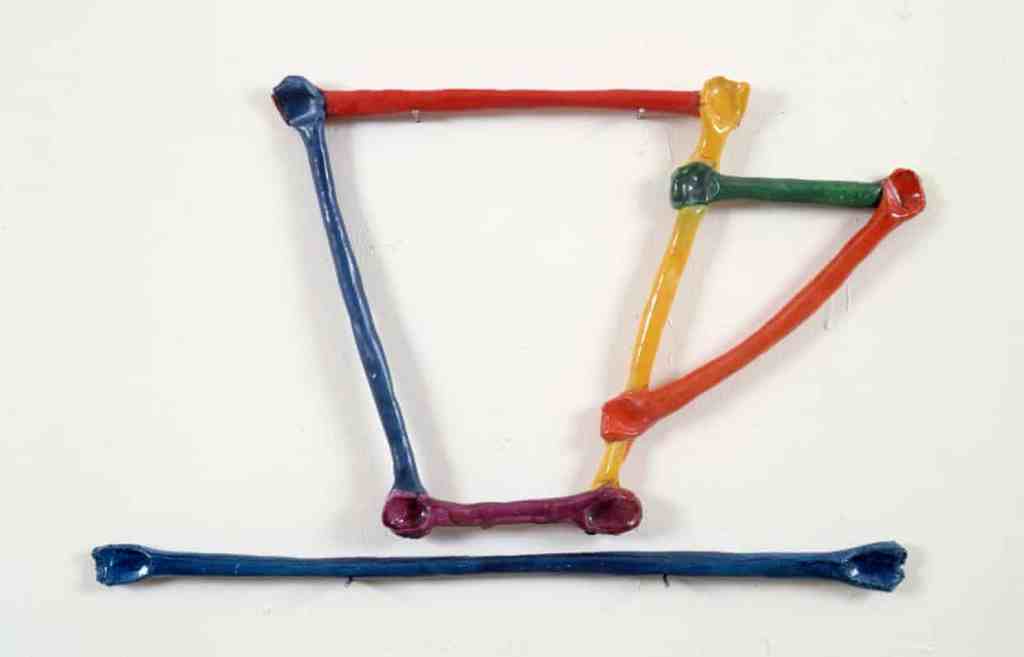

In trying to break or suspend objecthood the work of David Smith is held up as the prime example. His work occupies a space in which its part become entirely optical, part of ambient space but are still seen in terms of objecthood. The sculptor Anthony Caro’s work resists objecthood by imitating the efficacy of gesture.

To be able to defeat theatre literalist art degenerates in that the work only needs to be interesting. This is not a mark of quality. There is also a literalist preoccupation with time, with the duration of the experience which in turn is theatrical. The argument, essay, comes full circle in that in summary it states that we are all literalists most of our lives.

How does this resonate with my own experiences?

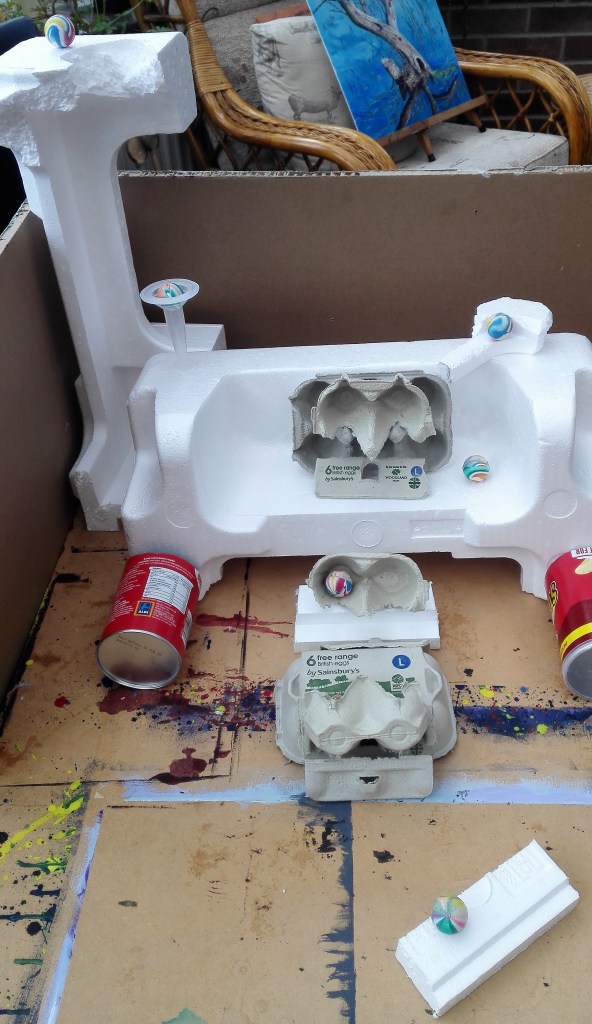

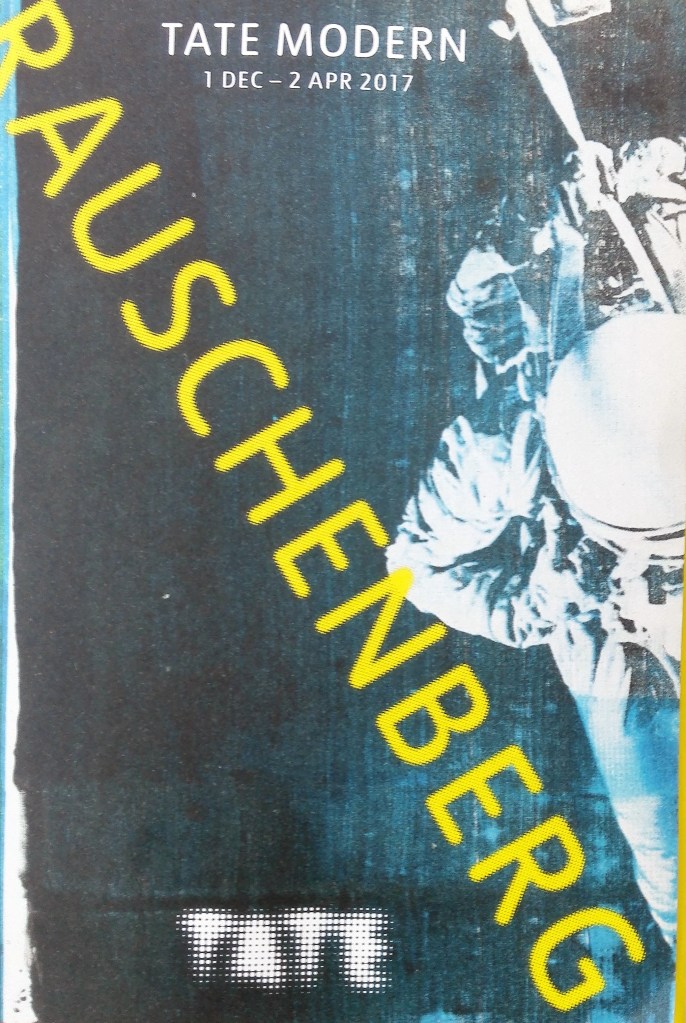

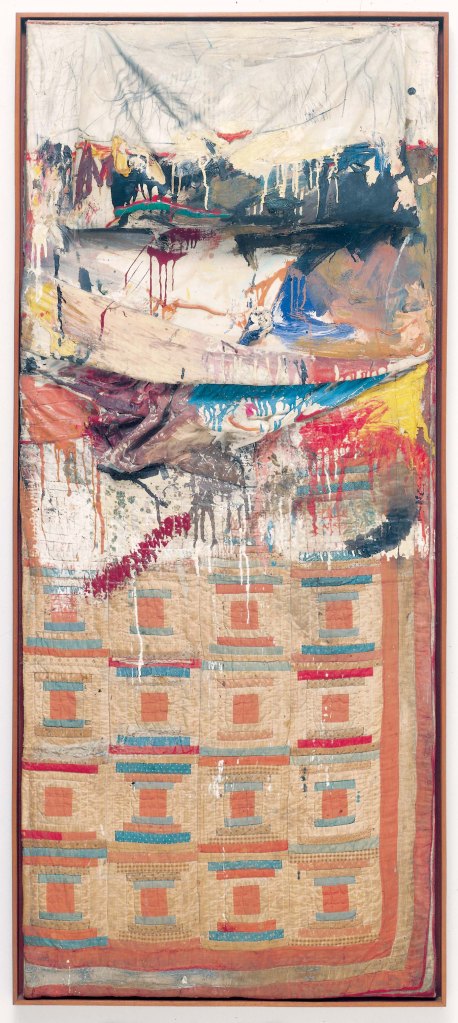

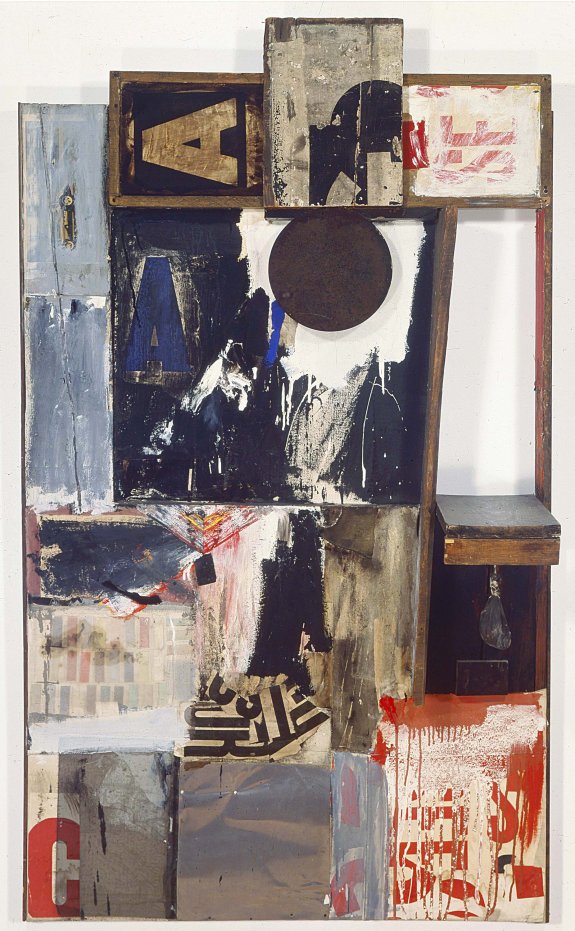

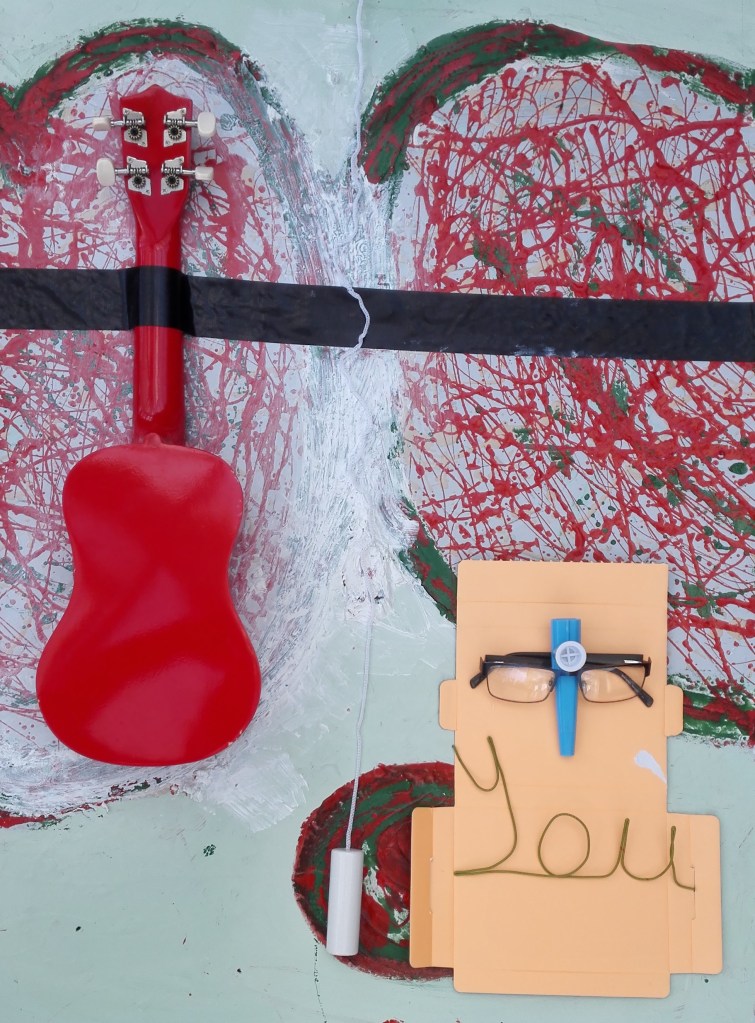

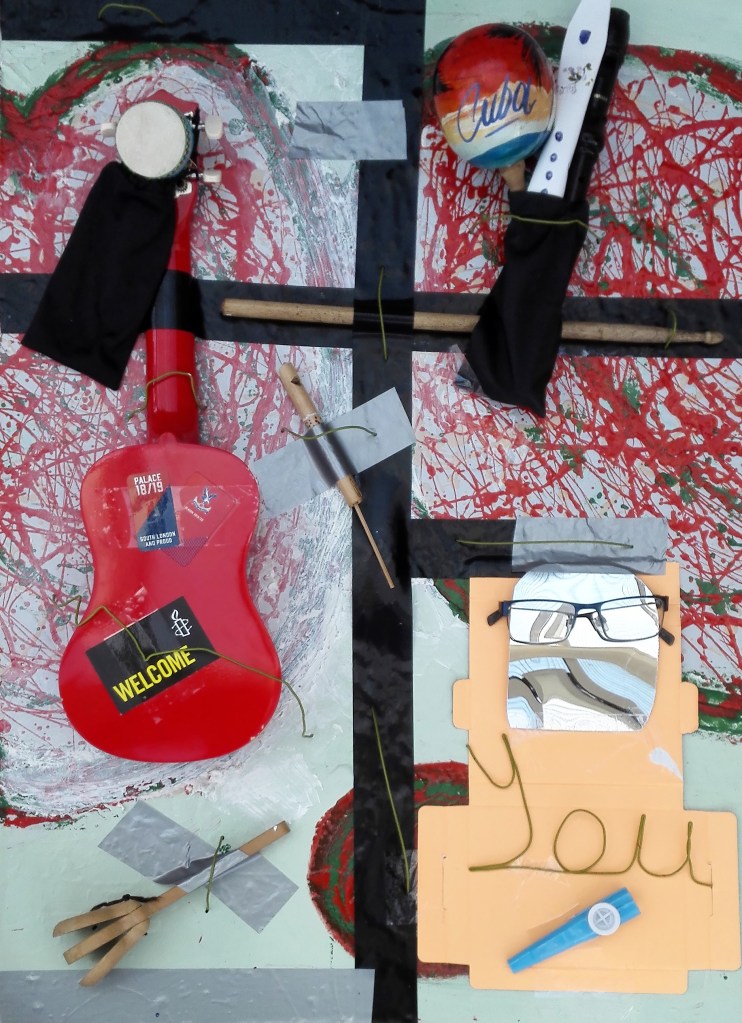

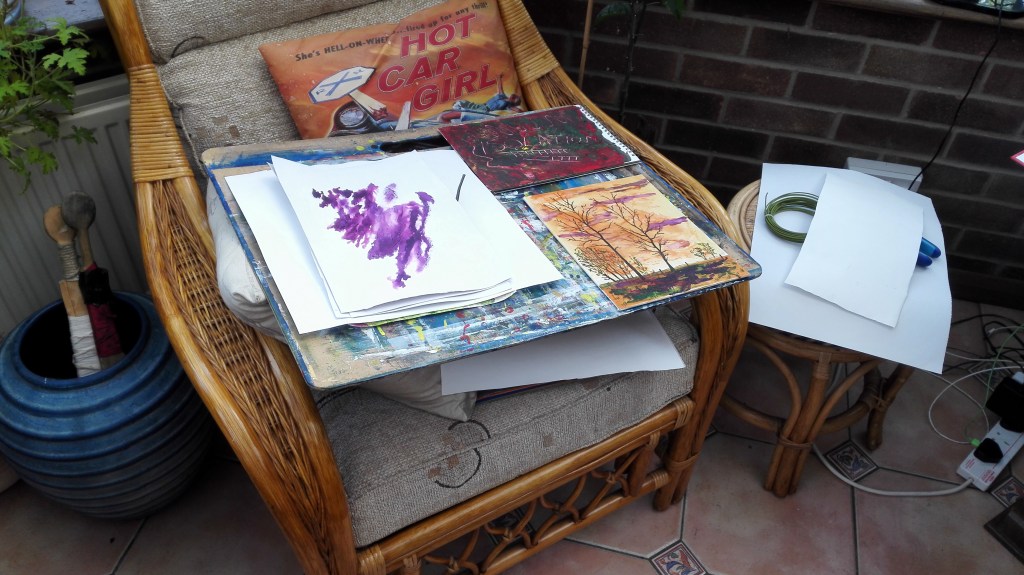

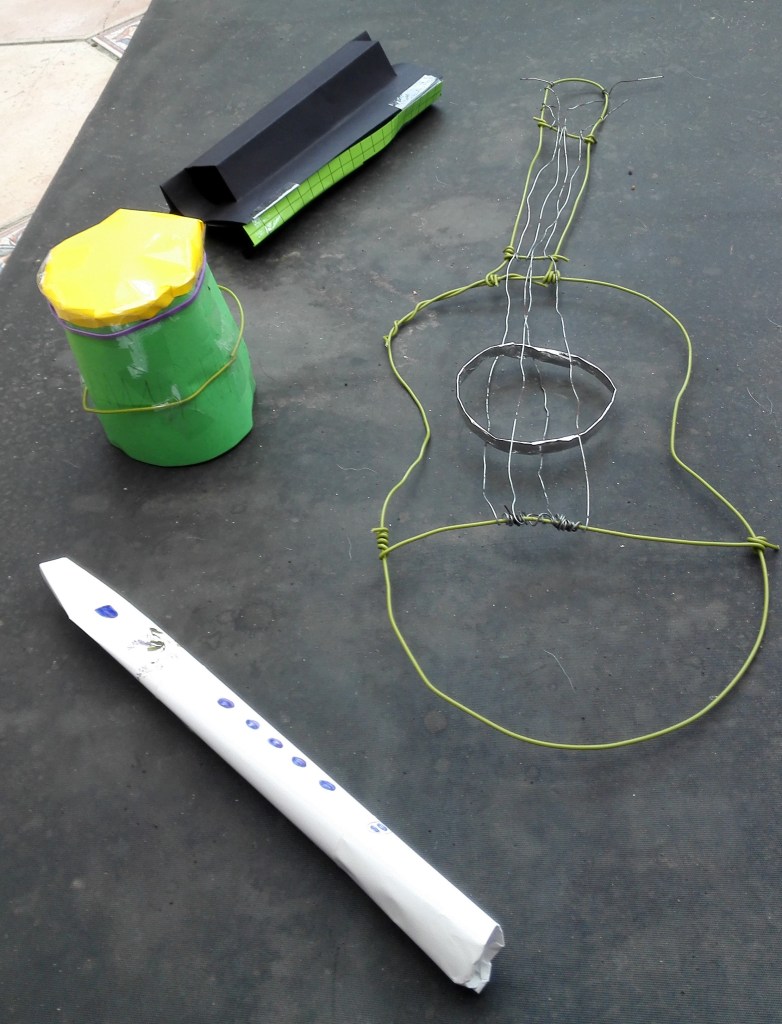

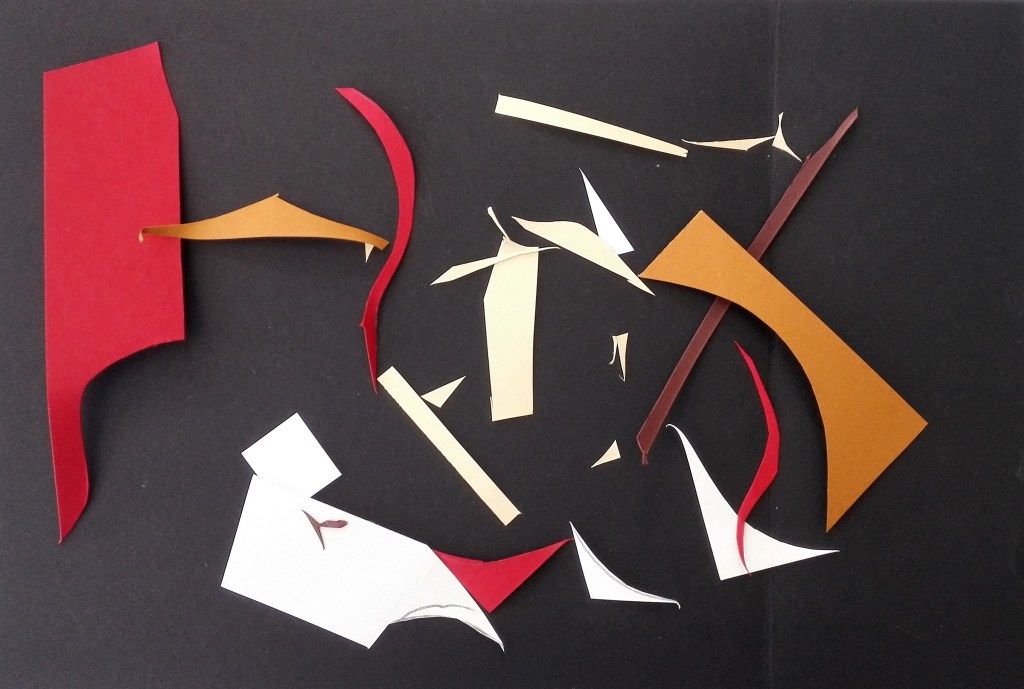

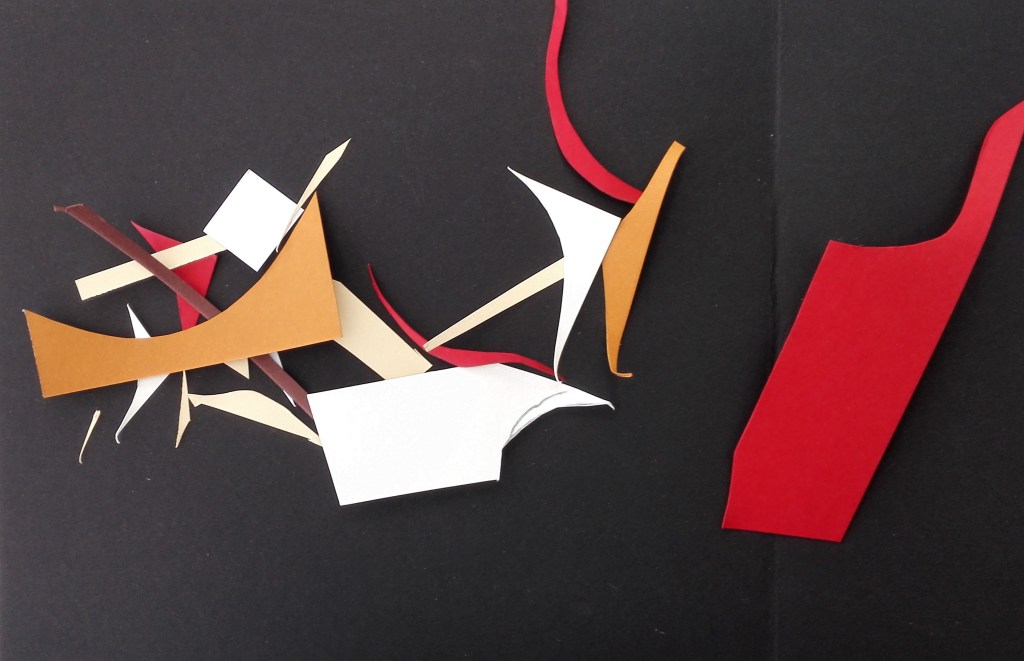

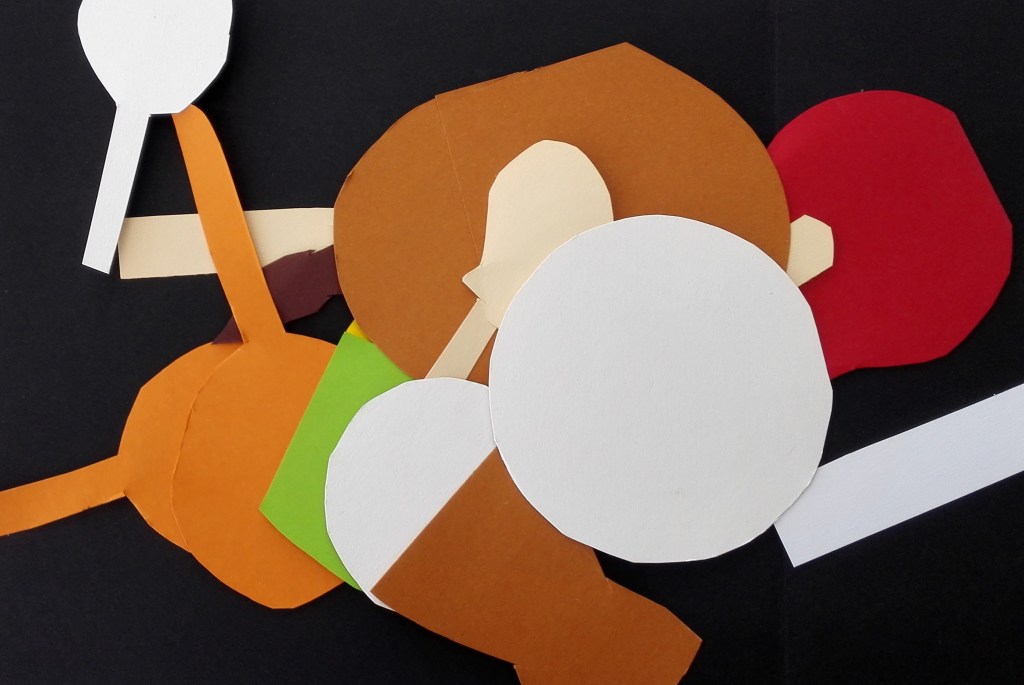

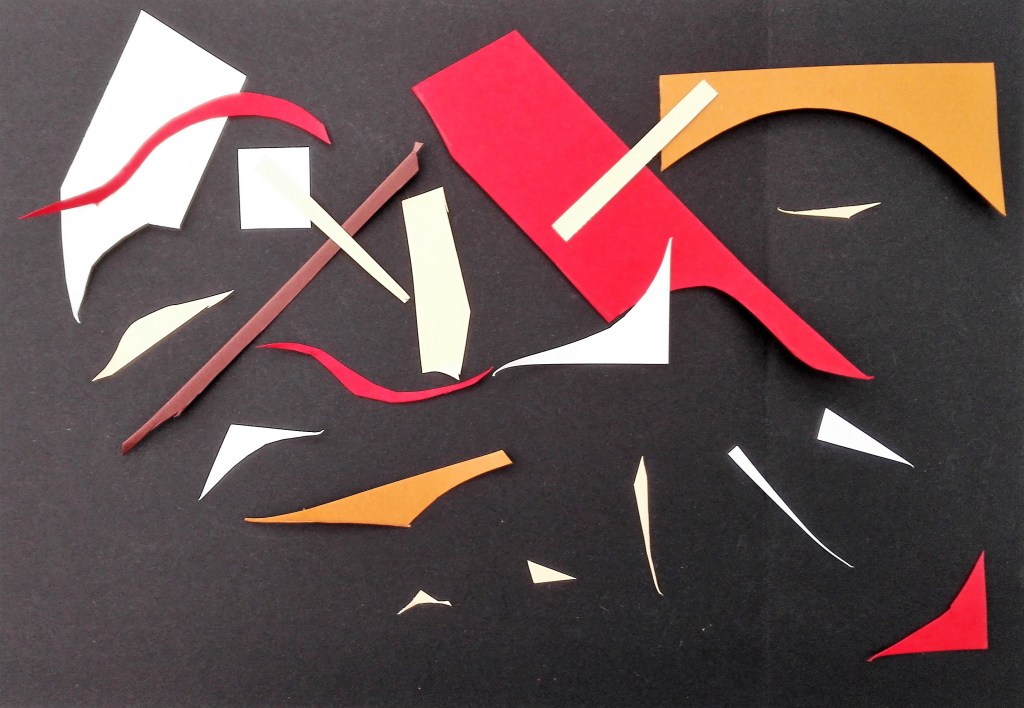

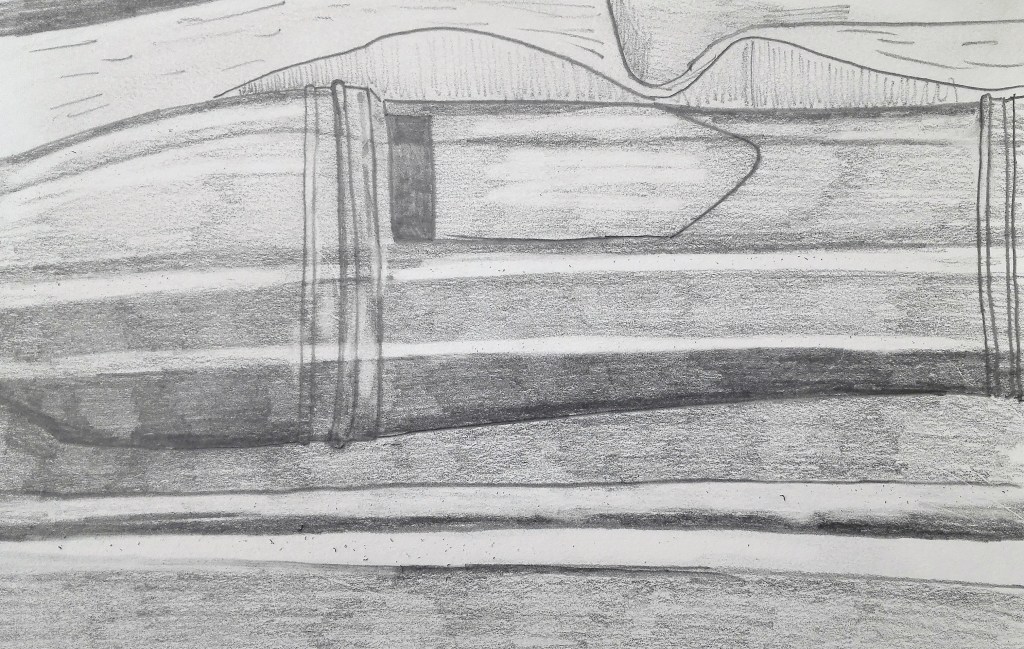

I can’t honestly say that I thought about my making during Part two in terms of literalist or minimalist art. I hadn’t considered questioning whether painting or even Combines were objects. They were the sum of their parts and presented as a work. I was trying to understand the language of working in a new way. Using new materials to create and assimilate into my work. It is only with hindsight that I can see parallels with the challenges that confronted artists such as Robert Morris in that I was considering the shape of objects. However I was nowhere near trying to limit the scope of the shapes down to simple geometric forms. That the literalists were trying to remove the association with anthropomorphism was contrary to what I was attempting. I wanted my work to be relatable and to contain gesture. I do remember having to consider the confines of the support. To me. the confines were in two dimensions and I didn’t really feel that I was working on a sculpture. This I feel was even true when working on the construction piece. I felt that I was assembling rather than sculpting.

My conclusion is that after reading the essay, and the points documented therein, I can see that the logical extension to pursuing a path of trying to simplify form and present work as an object removed from anything else would lead towards literalist or minimalist art. This was not a conscious consideration in my making. I was working to create pieces that had form and were, I hoped, aesthetically pleasing.