Paintings have the power to transport us through time, and they can act as a vehicle for our memory. These memories can be accompanied by a multitude of different feelings. A painting can act as a reminder of a time, a place or a shared experience, creating a bond between the artist and the observer. However both parties do not necessarily have had to have lived through the exact same experiences however. A common connection could be found in the subject of the painting, the place or the atmosphere that it evokes, for example the image of a dark austere looking building where the emotions that such an image conjures will be dependent upon our individual experiences. For some it will be foreboding or fear, for others it will be comfort and security. Whatever the emotion is, it is a part of our being, a memory. Additionally the feeling doesn’t need to have been experienced first-hand, it could, perhaps, be a scene from a film or a photograph, and however the emotion is no less real.

In this essay I will use the paintings of George Shaw and Peter Doig as my reference. Both have documented key periods of their lives in their paintings, in so doing they created a link to a shared past, not between them, but to us.

A consistent topic of George Shaw’s paintings has been the place where he grew up, Tile Hill, a suburb on the outskirts of Coventry, a subject with which he has been obsessed since he started painting. Whilst on a personal level I have no experience of Tile Hill the scenes that he paints are familiar to me, as suburban landscapes, similar to Tile Hill, exist all over the UK. His paintings portray the place as it was and is, with drizzly depictions of lock-up garages, muddy playing fields and uniform looking terraced houses on dull streets. These are the real images that are recalled by many that grew up in the UK in the late 20th century. His paintings are infused with memories of childhood and adolescence, of growing up, trying to fit in but remaining on the outside. His paintings do not reflect memory through rose tinted glasses but a realism that is at the same time nostalgic but refrains from being sentimental. What is it about these paintings that elicits these notions?

As an example, in the painting above Shaw has depicted a scene that could be found in suburban locations across the country. It is late autumn on a dull dank day and it appears that it has been raining. The frame structure for the swings takes centre stage but the swings themselves are missing. There is no fun to be had here today. The scene is framed by dark green foliage and leafless trees through which a row of identical terraced houses are just visible.

By contrast the paintings of Peter Doig draw on a wider range of influences. Which is predominantly due to his family’s constant moving house and location. Born in Scotland in 1959 his family moved to Trinidad in 1962 and then in 1966 to Canada. He then lived, studied and worked in London for 25 years before returning to Trinidad in 2002. All of these locations have informed his work. To quote Doig ‘When I was growing up, I never felt that I belonged anywhere because we never lived in a house for more than three months. That’s all I knew, and that’s why I don’t really belong anywhere.’ (i)

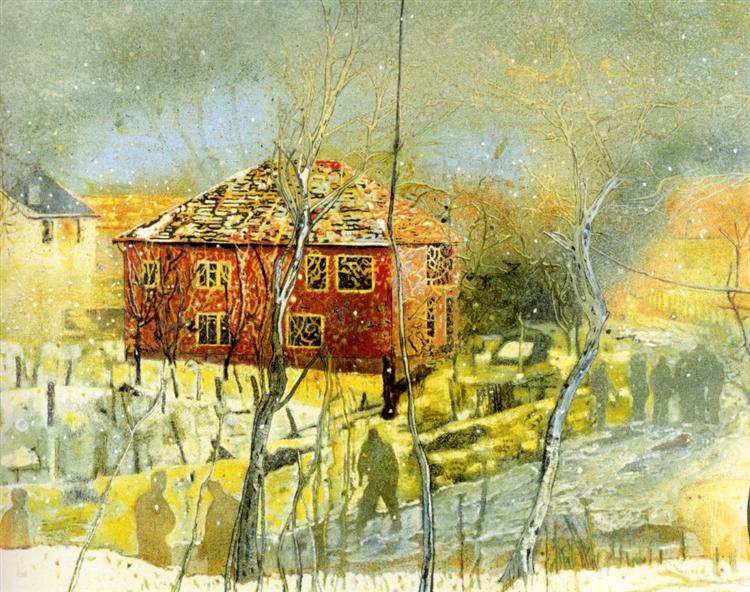

I have chosen to concentrate on the paintings inspired by his childhood and adolescence in Quebec, Canada. The reason for choosing this body of work is because they resonate with the imagery of childhood, houses viewed through trees in snowy landscapes. These paintings are not literal depictions of locations but are remembered scenes, many of which are seen through a veil of snow which acts in part as a filter representing the impact that the passing of time has on the memory, as it slowly becomes obscured from view. Similar to Shaw these paintings treat the subject without sentimentality.

As I delved deeper into the work of both artists I gained insight into how they have both been influenced by where they lived, grew up, the cultural influences of the time and the way that this is reflected in their paintings.

Starting with George Shaw and his depictions of Tile Hill there is an almost documentary appearance to the paintings, it is as if they are photographs taken on a Polaroid camera. The colours are muted, slightly faded, giving them a melancholic look which echo the passing of time. Tim Jonze in an article in the Guardian referenced a photograph of George trying to squeeze himself into a Joy Division T-shirt that he bought when he was 14 he stated that, ‘It’s a silly photograph, but also a moving one that explores, the passing of time, the roots of who we are and the melancholy of approaching middle age’ (ii). Shaw has also talked extensively about his pop culture influences, vinyl by The Fall, Two Tone pin badges, pulpy skinhead novels and Ladybird books about trees. The Ladybird books offer an insight into Shaw’s paintings in that they are illustrated with a similar lack of flamboyance. The pop culture references become clear when, referring to the additional artefacts on display at his exhibition at The Paul Mellon Centre in 2019, Shaw states that ‘I thought showing people these influences might be more interesting than everyone thinking it all came from Constable or Turner. My entry level into Romanticism was (Factory Records designer) Peter Saville. It wasn’t the National Gallery’ (iii). Additionally when talking about his visits to galleries, with his Dad, he states that the paintings they constantly painted said ‘nothing to him about his life’ (iv) referencing lyrics from a song by The Smiths.

Two further quotes by Shaw which I feel indicate what his Tile Hill paintings are about. The first from an interview with Sue Hubbard, Shaw states that his paintings reflect ‘a dream of Britain, an island I have come to know as a landscape of ghosts and haunted houses, of fair to middling weather and stony prehistory but also a backdrop for injustice, criminality, humour, suspicion and sparse grace’(v) The second commenting on his hometown in an article by Lydia Figes in Art UK ‘I don’t think it has ever left me, that sense of possibility and familiarity and possible danger lurking out there somewhere beyond. I haunted the place and now it haunts me.'(vi)

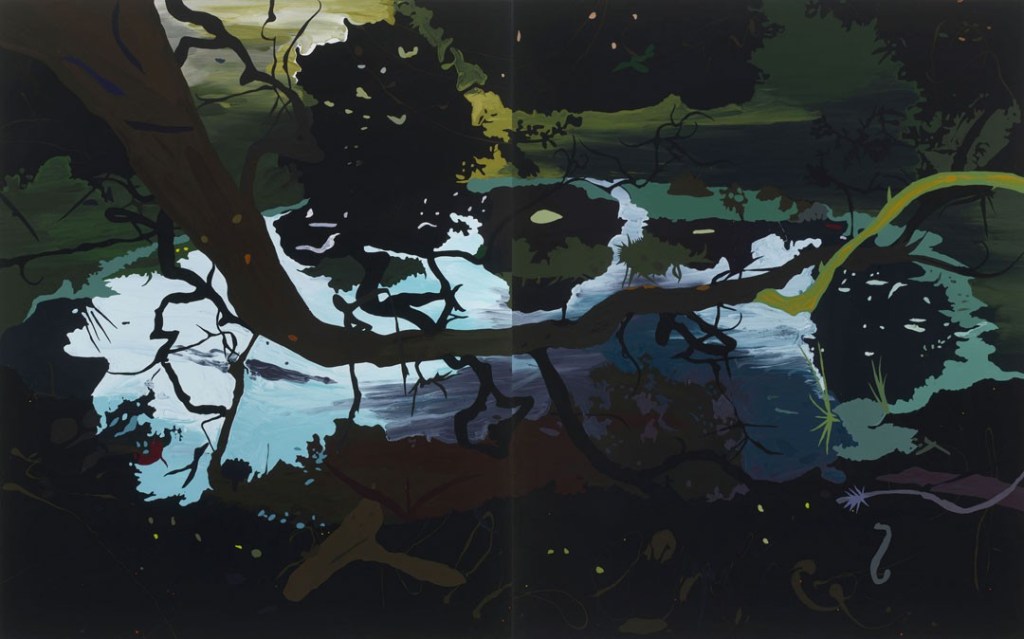

Peter Doig’s adolescence and upbringing is a stark contrast to George Shaw’s and this is apparent in his paintings that reference this time in his life. Looking at his paintings of the Canadian landscape they are less about place and more about atmosphere and feeling, an interesting comment by Doig which illustrates this point was referenced in an article exploring his key works, ‘Progression of Art’. Reflecting on his Canadian tree-scape paintings Doig said ‘The tree line is a mixture of what I could see from my working space in my parent’s barn, where I made sketches of northern-looking pines and dying trees.’(vii) This is further reinforced by Katherine Arnold of London auction house, Christies, who stated ‘In taking up archetypal images of Canada’s landscape, Doig sought to distance himself from its specifics. These were not paintings of Canada in a literal sense, but rather explorations of the process of memory. For Doig, snow was not simply a souvenir of his childhood, but a conceptual device that could simulate the way our memories may be transformed and distorted over time.’(viii) The cultural references in Doig’s paintings of Canada are also informed by cinematic and theatrical devices which he uses to create nostalgia, ambiguity and mystery. An example of this, which was touched upon in the extract from Katherine Arnold, is the use of snow in these paintings. “Snow draws you inwards” Doig once said. A technique that has been used in numerous films to indicate the blurring of memory is the use of snow to create a barrier between the viewer and the subject. This use of snow to create a barrier becomes a signal of the gap between the past and now. The buildings in Doig’s Canadian paintings are often viewed through a tree-scape, his technique is to paint the houses through the trees rather than paint the house put the trees over it. As he comments in an interview with Robert Enright in 2006 ’it was more about looking and picking out bits with the eyes.’ (ix) As with memory we pick out what we remember and piece it together.

In the painting above the Red House dominates the scene with its solid form and strong colour. It is surrounded by images that seem to shift and fade in and out of view. There are shadowy figures, a frozen pond, wispy trees and a shimmering white house all of which are diffused by a soft light and falling flakes of snow. The painting indicating a strong memory that has become dislocated due to the passing of time.

In trying to draw conclusions and comparisons in how both artists approach the subject of memory in their paintings I am conscious that we all experience the world in our own way, we have different lenses and a multitude of varying experiences. The ability to be able to highlight and communicate the commonality that is shared is what draws the observer into these paintings and holds their attention. These paintings create a shared connection which resonates beyond the image.

With Shaw’s paintings of Tile Hill it is more than simply the image itself. The pop culture references, which are not implicit in his paintings, draw on a certain Britishness that runs from the Kitchen Sink dramas of the 1960’s to the anger of Punk, the intellectual writing lyrics and imagery of Post Punk through to Two Tone. A connection is made to the dystopian mournfulness of Joy Division, the rantings and imagery of The Fall through to the poetry of The Smiths and the despair but optimism of The Specials. All of these performers are born from the same sense of wanting to communicate what it was like to live through this time. They pull the same strings in our collective memory, evoking the bleakness of these times. Thatcherism was wreaking havoc with working class lives and was decimating traditional industry. Despite this, it is the beauty found in the familiar and seemingly mundane scenes that invoke our collective memory, especially since clear parallels can be drawn to the present. Shaw was reticent to make further paintings of Tile Hill but after visiting his mother, who still lives there, he once again captured images using photography for his reference. He toyed with his emotions for some time, reluctant to return to the subject, but unable to resist, he made a further series of paintings. One of which ‘The man who would be king’ depicts an English flag draped in the window of a block of flats which sums up the depression, desolation and xenophobia that drove the UK to Brexit.

Peter Doig’s paintings don’t exist in any particular time or place. They inhabit their own space. The transient nature of Doig’s time in Canada, never putting down roots, is represented in the way that the paintings seemingly exist in their own space. Unlike Shaw the specific location of the images can’t be identified, instead they appear as a dreamlike mixture of references which make connections to us. They are made up of new places, far off places, forgotten places. Where Shaw’s paintings draw direct references, Doig’s references are ambiguous, these are fictional places in which we can imagine we might inhabit. The shadowy figures, that are often present, represent ourselves, these figures help to draw you into Doig’s world. With Shaw’s paintings the observer is placed on the outside looking in, however with Doig’s we are located within the painting.

In the painting above we are taken back to a specific place and memory in Doig’s childhood. The title indicates the location, Cobourg is a town in the Canadian province of Ontario however there is nothing in the painting to specifically identify the town. The figures, 3 + 1 more, blurred from our direct gaze by the falling snow, must be Doig and his family looking out at us from the past. The plus one being Doig himself indicating his feeling of not quite belonging.

The two artists explored here involve memory to make the connection to us, however the way that they do so is entirely different, but both harness nostalgia without being sentimental. It is for the observer to locate their personal response to the paintings, to let the images take them back to their memories. The approach of Shaw and Doig to the subject of memory are different, in that George Shaw’s paintings are about a time and place whereas Peter Doig’s paintings have a more timeless quality. Both approaches are valid, it is for the observer to infer their own personal response.

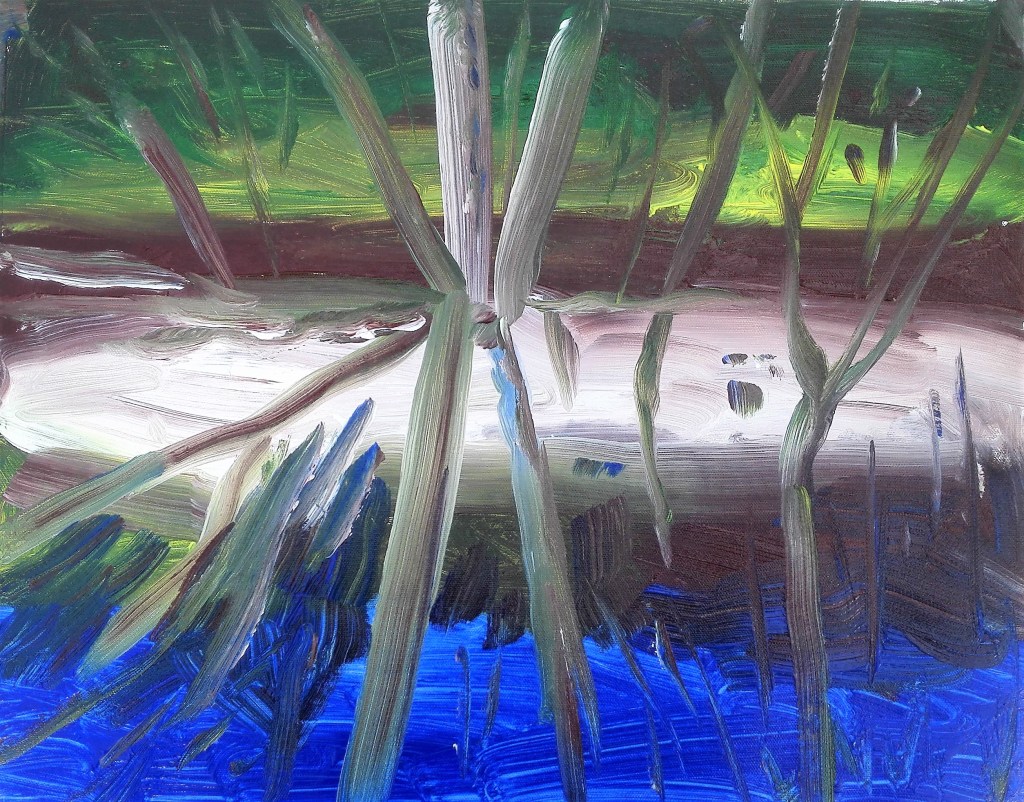

In my own practice I am trying to capture the impact of passing of time and the effect that it has on man-made objects and their place in the landscape. I am interested in the transition from fully functional to disregard and the memories that attach themselves to the stages of this process. I imagine the stories that these objects have witnessed, what have they seen? Where they have been? In the example below my painting ‘Winter break’ shows an abandoned caravan. It has seen better days but is now in a state of poor repair. The elements are in the process of finally reducing it to nothing. At some point it was loved, a place of security and rest, but what was it used for? Perhaps initially for holidays at the coast then in its latter stages as a seasonal farmworkers temporary dwelling. It exists as a memorial to the events and lives lived slowly fading as the caravan transitions and imperceptibly disintegrates in to the past.

List of illustrations:

- George Shaw, Scenes from the passion – The Swing, Enamel on canvas, 70 x 101cm, 2002/03, University of Warwick Art collection

- Peter Doig, Red House, Oil on canvas, 200 x 249.8 cm, 1995/06

- George Shaw, The man who would be king, Enamel on canvas, 46 x 55 cm, 2017

- Peter Doig, Cobourg 3 + 1 more, Oil on canvas, 200 x 250 cm,1994

- Mark A Taylor, Distant holidays, Aqua oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches, 2020

Bibliography:

‘i, Peter Doig quote source unknown

‘ii, Tim Jonze , Guardian article 13/2/2019, Anarchy in Coventry: George Shaw’s greatest hits | George Shaw | The Guardian

‘iii, Tim Jonze , Guardian article 13/2/2019, , Anarchy in Coventry: George Shaw’s greatest hits | George Shaw | The Guardian

‘iv, Tim Jonze , Guardian article 13/2/2019, , Anarchy in Coventry: George Shaw’s greatest hits | George Shaw | The Guardian

and Morrissey, Marr (1986), Panic. In: The world won’t listen (1987), Rough Trade

‘v, Sue Hubbard, 4/12/2018, George Shaw’s Homely and Unsettling Vision of Great Britain, George Shaw’s Homely and Unsettling Vision of Great Britain – ELEPHANT

‘vi, Lydia Figes in Art UK, 23/3/2020, The paintings of George Shaw: an unconscious foreshadowing of Britain during quarantine, The paintings of George Shaw: an unconscious foreshadowing of Britain during quarantine | Art UK

‘vii, Peter Doig quote when discussing his 1989/90 painting ‘Milky Way’ , Peter Doig Artworks & Famous Paintings | TheArtStory

‘viii, Katherine Arnold, Christies Auction House, quoted when discussing 1991 painting ‘Charley’s space’ Peter Doig Artworks & Famous Paintings | TheArtStory

‘ix, Robert Enright, Border Crossings Magazine June 2006, The Eye of the Painting: An Interview with Peter Doig